You may be walking or driving around and noticing that some trees have started to show some fall color lately. Well, let’s put those pumpkin spice lattes on hold for a few more weeks, because this is actually a stress response to the lack of rain we had this summer.

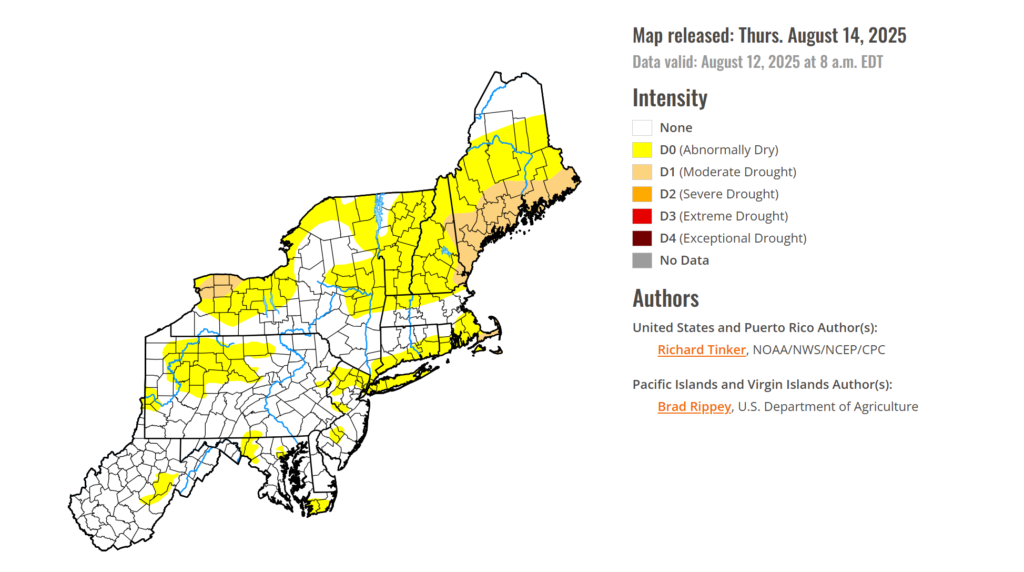

New England is experiencing abnormally dry conditions that are increasingly affecting the region’s ecosystems—particularly its trees. According to the latest data from the U.S. Drought Monitor (see image above), large portions of Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and southern New Hampshire and Maine are currently classified as “Abnormally Dry” (D0), with major pockets of Moderate Drought (D1) in more affected areas (in New Hampshire Seacoast and Coastal Maine).

This growing dryness is more than a seasonal inconvenience; it is having visible and damaging effects on tree health, orchard productivity, and long-term resilience of New England’s forests and landscapes.

The U.S. Drought Monitor, a joint effort by the National Drought Mitigation Center, NOAA, and the USDA, shows that much of coastal New England is experiencing below-average precipitation, with soil moisture and groundwater levels steadily declining. For several key cities in the region—including Newburyport, MA; Portsmouth, NH; Dover, NH; and Portland, ME—this marks one of the driest late summers on record.

While these conditions may not reach the severity of past widespread droughts, even a classification of “abnormally dry” is enough to impact both short-term plant health and long-term ecosystem balance.

You may be wondering, whose is at risk here? It is just a little dry out there. Well here are a few things you might want to think about:

1. Reduced Fruit Production

I’ve been getting a lot of calls about this one. During drought stress, fruit-bearing trees divert energy away from reproduction (i.e., producing fruit) and instead focus on basic survival functions. As a result, orchard owners and backyard gardeners may notice fewer blooms, smaller fruits, and weaker yields, particularly in apples, pears, peaches, and berries that dominate many New England orchards.

2. Early Fall Coloring and Premature Defoliation

One of the more visible effects of drought is early fall coloring. Trees begin to shut down photosynthesis early when moisture is scarce, leading to premature leaf color change and drop. While this may seem like a quaint sign of autumn , it is actually a stress response—and if repeated annually, it can weaken trees over time. Trees that especially love to have wet feet (roots) are nutorious showing early fall color when drought stressed (i.e. birches, maples, & black tupelos).

3. Increased Risk of Winter Burn

Trees stressed by drought in the summer and fall are more susceptible to winter burn, a condition in which evergreen foliage (and sometimes bark) dries out during cold, sunny winter days. Without adequate moisture in the soil, trees are unable to replenish the water lost through transpiration, leading to browning, dieback, and in some cases, death of limbs or whole trees by spring.

To help mitigate the impact of abnormally dry conditions on trees and shrubs, we recommend:

- Deep, infrequent watering (especially during dry stretches in late summer and fall)

- Mulching around root zones to help retain soil moisture

- Avoid fertilizers high in macro nutrients. Settle for humic acids or kelps to aid in reducing stress.

- Monitoring trees for signs of stress, including wilting, scorched leaf edges, or early leaf drop

The current situation, as highlighted by the U.S. Drought Monitor, is a clear reminder of the complex and often delayed consequences of drought on our natural systems.

Healthy trees are more than just a landscape feature—they are a critical part of local agriculture, wildlife habitat, and climate regulation. As conditions continue to evolve, proactive care and attention will be essential to protect New England’s green heritage.